ASSAP News 128 (Winter 2009-10), 11; Skeptical Adversaria 1 (2010), 4-6

Reproduced with permission

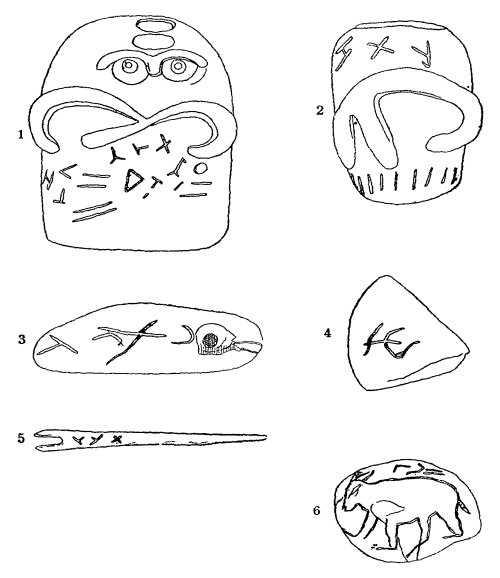

During the 20th Century, an allegedly mysterious archaeological site at Glozel in France received much intermittent attention. It was originally promoted by local ‘discoverers’ in the 1920s, and despite determined debunking (notably in the pages of Antiquity ) it continued to ‘rear its head’, especially when thermo-luminescence dating suggested that it was genuinely ancient. Now it has resurfaced again. Lionel & Patricia Fanthorpe have recently commented on Glozel in ASSAP’s newsletter, focusing on the script (if so it be) found on tablets associated with the site.

However, it remains the case that most scholars who have examined the case of Glozel are far from persuaded that the site itself is genuinely ancient. The finds are altogether unlike anything genuine unearthed in the area, and it is not surprising that forgery/’salting’ was rapidly proposed as an explanation. Now it is difficult at this remove to be sure of people’s motives, and I am not myself convinced that those who first reported the site were fraudsters. None of the firm dates arrived at by thermo-luminescence or the various other tests which have been applied are themselves modern. But they do show a wide range; and even the early/middle part of the range, historically the least implausible section, implies an otherwise unknown mini-civilisation, with an otherwise unknown script and possibly an unknown language, in the middle of Celtic/Roman Gaul. This would be very strange, especially if the tablets themselves were somehow genuine (see below). So maybe the site was salted (by persons unidentified) but with old materials (?).

On the linguistic side of the case, specifically: the Fanthorpes refer to the supposed Glozel script as an ‘alphabet’. This would imply that it has approximately one symbol per speech sound. But an undeciphered ‘script’ such as this might instead be a syllabary (one symbol per syllable, as in Japanese kana) or a logography (one symbol per word/stem, as in Chinese); and there are yet further possibilities. There are statistical tests which can provide some indication of script-type: e.g., the ratio of tokens to types (much higher for an alphabet with its small number of symbols than for a logography), typical text-length, complexity of symbols (alphabetic characters tend to be simpler than logograms), sheer total number of different symbols, etc. The total number of sign-types is over 130, which virtually excludes an alphabetic analysis. But in fact the more sophisticated tests of this kind which have been applied to the Glozel ‘script’ (chiefly by the linguist Crawford) suggest that the ’texts’ are not linguistic at all. For instance, the fact that 34 of the 130+ distinct signs occur only once each is highly suspect; such patterns are vanishingly rare, in syllabaries (where the distribution of signs is usually much more even) and in logographies (where rare words are seldom so thick on the ground). This suggests that the system is either a fake produced by someone unaware of these considerations, or, if genuine, not a script as such (i.e. it does not represent any language).

My main general point is thus that on current evidence one should not assume that the site, specific artefacts or, especially, the tablets are genuinely old.